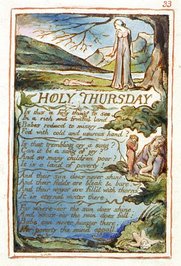

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Is this a holy thing to see

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduc'd to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

Blake's opening stanza serves as a furious riposte to the multitude of aristocratic voices who, pointing to the growth of agriculture and church-attendance at the close of the eighteenth century, asserted that England had become wealthy and virtuous.

As always in his work, Blake is determined to tell us that church-going does not automatically equate to goodness: in fact, the church's self-satisfaction blinds it to the damage it does to the innocent.

What is "Holy Thursday"?

"Holy" or "Maundy" Thursday refers to the Last Supper of Jesus and his disciples as recorded in the biblical New Testament. One particularly significant episode during that event was that of the master's washing of his disciples' feet - an act which signified the utmost humility in service. English monarchs and the wealthy traditionally used this festival for symbolic acts of charity: with the complementary poem in "Songs of Innocence", Blake pictures such an act, of which he appears to approve, carried out in St. Paul's Cathedral.

However, our appreciation of the "wise guardians of the poor" thus advertising their charity may not be wholly shared by Blake's "Piper", the supposed narrator of the "Songs of Innocence". In their state of innocence, children should not be regimented; rather, they should be playing blithely on the "ecchoing green". The children in this poem 'assert and preserve their essential innocence not by going to church, but by freely and spontaneously, "like a mighty wind," raising to "heaven the voice of song." ' (Robert F. Gleckner: Point of View and Context in Blake's Songs - included in "Twentieth Century Views: Blake, A Collection of Critical Essays." Ed Northrop Frye: Prentice-Hall Inc. 1966)

Is that trembling cry a song?

Can it be a song of joy?

And so many children poor?

It is a land of poverty!

With his "Holy Thursday" of the "Songs of Experience", Blake's "Bard" clarifies his view of the hypocrisy of formalised religion and its claimed acts of charity. He exposes the established church's self-congratulatory hymns as a sham, suggesting in his second stanza that the sound which would represent the day more accurately would be the "trembling cry" of a poor child.

The poet, as Bard, states that although England may be objectively a "rich and fruitful land", the unfeeling profit-orientated power of authority has designed for the innocent children suffering within it an "eternal winter". The biblical connotations of the rhetorical opening point us towards Blake's assertion that a country whose children live in want cannot be described as truly "rich". With the apparent contradiction of two climatic opposites existing simultaneously within the one geopolitical unit, we are offered a metaphor for England's man-made "two nations".

The righteous anger which drives the work implicitly denies the claims of the established church - which Blake condemns as complicit in creating poverty - to be "holy".

And their sun does never shine,

And their fields are bleak & bare,

And their ways are fill'd with thorns:

It is eternal winter there.

If one is starving and neglected, whatever the calendar might say about the season, the experience is that of living without sun or harvest. The image of thorns blocking one's path was, for the poet's Bible-wise readers, immediately recognisable as deeply defeating and depressing.

Blake was writing during the "agricultural revolution", whose pioneers congratulated themselves upon their vigorous increases in output. The poet argues that until increases in production are linked to more equitable distribution, England will always be a land of barren winter.

For where-e'er the sun does shine,

And where-e'er the rain does fall,

Babe can never hunger there,

Nor poverty the mind appall.

As a symbolic poet, Blake tries to tap into what he sees as the energies which lie behind each icon. We may look up and imagine we see that familiar ball of hydrogen undergoing its constant thermonuclear process in the sky; we may feel what seems to be water falling upon us: but in symbolic terms their tedious physicality is meaningless.

The shining sun and the falling rain represent the generosity of the natural world which humankind has spurned. Only when people live in happiness can we claim that their world is rich.

Understood metaphorically, the final stanza tells us that in a land of life-giving sun and rain there would be no class condemned to starve.